If you’ve ever felt overwhelmed by memories, emotions, or triggers that bring you back to a painful experience, you’re not alone. Trauma can leave lasting marks on both your body and mind, causing automatic responses that aim to shield you from further harm. These are called trauma responses, and they can show up in your daily life, affecting your relationships, work, and sense of self.

Understanding these trauma responses is key to breaking free from the patterns that hold you back. In this blog, we’ll dive into what trauma responses are, the different types, and how to manage them.

Feeling overwhelmed by responses to past trauma? Contact Monima Wellness today to learn more about our outpatient trauma treatment programs for women in San Diego. Let us guide you on your journey to recovery.

Understanding Trauma

Before we explore trauma responses, it’s important first to understand what trauma is. Trauma is a deeply distressing experience that overwhelms an individual’s ability to cope, often leaving lasting emotional, mental, and even physical scars. Trauma can stem from a variety of events, such as accidents, abuse, violence, or witnessing something traumatic. When unprocessed, it can affect how someone feels, thinks, and reacts long after the event has passed.

There are three primary types of trauma:

- Acute trauma – Resulting from a single stressful or dangerous event.

- Chronic trauma – Stemming from repeated and prolonged exposure to distressing situations, like domestic violence or long-term abuse.

- Complex trauma – Occurring from exposure to multiple traumatic events over time, often interpersonal, such as childhood abuse or neglect.

Learn More About Trauma Treatment

A Word About ‘Big T’ and ‘Little t’ Trauma

Historically, trauma has been categorized into “Big T” and “Little t” trauma. Big T trauma refers to significant, life-threatening events like natural disasters or assaults. In contrast, Little t trauma encompasses less overt yet still distressing experiences, such as relational conflict or loss.

This distinction has become less widely accepted in mental health treatment today. Modern trauma therapy recognizes that both types of experiences can have profound impacts on an individual’s mental health, regardless of the event’s perceived “size.”

Trauma is personal, and the event itself does not determine its effects but how it’s experienced and processed. Understanding this shift encourages a more inclusive view of trauma, allowing for more recognition of traumatic events without minimizing their emotional impact.

What Is a Trauma Response?

A trauma response is how your body and mind react when faced with something that feels like a threat, often linked to a past traumatic experience. It’s a survival mechanism controlled by your nervous system, designed to protect you in moments of danger.

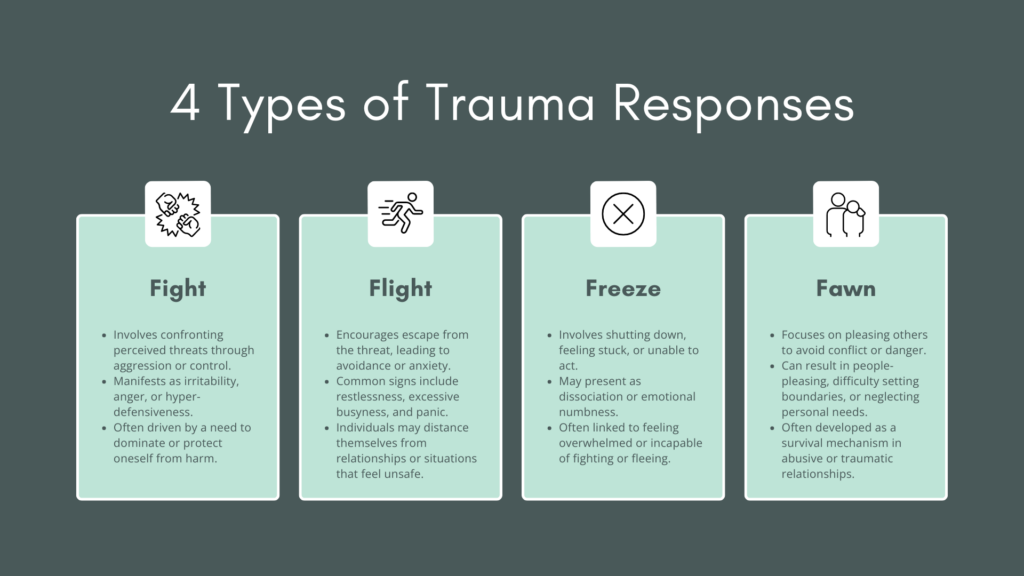

The most common trauma responses are fight, flight, freeze, and fawn. These are automatic reactions that helped our ancestors survive threats, but they can become problematic when your body continues to react this way, even when the trauma is no longer present. Over time, living in a constant state of alert can make everyday situations feel overwhelming and challenging to manage.

If you’re feeling stuck in a pattern of trauma responses, understanding these reactions can be the first step toward healing.

Related: Do I Have PTSD? Quiz

The 4 Types of Trauma Responses

1. Fight Response

The fight response kicks in when your body feels the need to defend itself. It’s your way of confronting a perceived threat head-on, often through assertiveness or even aggression. While this can be helpful when real danger is present, for individuals with unresolved trauma, the fight response can show up in situations where there isn’t an actual threat.

Common signs of a fight trauma response might include:

- Irritability or aggression

- Frequent anger outbursts

- A strong need for control

- Being constantly on alert (hypervigilance)

2. Flight Response

The flight response is your instinct to escape when faced with a perceived threat. It often leads to avoidance, even when no real danger exists. When someone is stuck in the flight response, they may feel an overwhelming urge to flee from anything that reminds them of past trauma, whether it’s a place, person, or situation.

Signs of a flight trauma response include:

- Anxiety or panic attacks

- Overworking or staying excessively busy to avoid uncomfortable emotions

- Avoiding specific people, places, or situations

- Feeling restless or unable to relax

If you’re constantly avoiding things that trigger discomfort or anxiety, it may be your flight response taking over. Recognizing this pattern can help you understand and manage these behaviors.

3. Freeze Response

The freeze response is like the “deer in headlights” reaction. When faced with overwhelming fear or trauma, your body might shut down, leaving you feeling stuck or unable to respond. This can happen both during a traumatic event and in everyday situations when you’re triggered by reminders of that trauma.

Signs of a freeze trauma response include:

- Feeling stuck or indecisive, unable to move forward

- Dissociation, or feeling disconnected from your body or surroundings

- Inability to take action, even when you know it’s needed

- Numbness or emotional detachment

If you find yourself freezing or feeling paralyzed in moments of stress, it’s likely a freeze response taking over. Acknowledging this reaction can help you begin to regain control in those moments.

4. Fawn Response

The fawn response is less recognized but just as important. It involves pleasing others or avoiding conflict to stay safe. This reaction often develops in people who have experienced abuse or unhealthy relationships, where keeping the peace is crucial to preventing further harm. Instead of confronting or fleeing a situation, someone in a fawn response will focus on appeasing others.

Signs of a fawn trauma response include:

- People-pleasing behaviors

- Difficulty saying no or setting healthy boundaries

- Putting others’ needs above your own

- Suppressing your feelings or opinions to maintain peace

If you often prioritize others to avoid conflict or feel the need to please at the expense of your well-being, the fawn response may be at play. Recognizing this pattern is crucial in learning how to set boundaries and reclaim your voice.

Managing and Treating Trauma Responses

Managing trauma responses starts with understanding that healing is possible, and there are several approaches you can take on your own to begin the process. While therapy plays a significant role in trauma recovery, there are also practical steps you can take in your daily life to manage these responses and start feeling more in control.

1. Trauma-Informed Therapy

For more profound healing, professional therapy is one of the most effective ways to address trauma responses. Here are some of the best types of treatment that can help manage trauma:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): This therapy focuses on identifying and changing harmful thoughts and behaviors linked to trauma. CBT is highly effective in addressing trauma responses such as anxiety and avoidance by helping you challenge and reframe negative thoughts.

- Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): EMDR helps process traumatic memories in a way that reduces their emotional intensity. This therapy has been particularly successful for people struggling with trauma-related flashbacks or overwhelming feelings tied to past events.

- Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT): DBT combines mindfulness, emotion regulation, and interpersonal skills training to help individuals manage overwhelming emotions. It’s beneficial for people experiencing intense trauma responses like dissociation or difficulties with emotional regulation.

Learn More About How We Treat Trauma

2. Self-Care and Mindfulness Practices

Incorporating self-care and mindfulness into your routine can help manage trauma responses and reduce anxiety:

- Mindfulness and meditation: Mindfulness practices encourage staying present, which can be powerful for managing trauma-related hypervigilance and anxiety. Techniques like mindful breathing, body scans, and guided meditation help you stay grounded and calm your nervous system.

- Physical exercise: Movement, such as trauma-informed yoga, walking, or other physical activities, can help release tension and restore a sense of safety in your body. Exercise reduces stress hormones and improves mood, helping alleviate symptoms like restlessness or fatigue.

- Journaling: Writing down your thoughts and feelings can help you process your trauma. Journaling allows you to safely express your emotions, track your progress, and identify any patterns in your trauma responses.

3. Building Healthy Boundaries

For those struggling with the fawn response—people-pleasing to avoid conflict—learning how to set and maintain healthy boundaries is essential. This could involve:

- Practicing saying “no” when you feel overwhelmed.

- Prioritizing your needs and self-care.

- Recognizing when you’re sacrificing your well-being to maintain peace with others.

Over time, boundary-setting becomes easier with practice and builds confidence in maintaining healthier relationships.

4. Creating a Support System

You don’t have to navigate trauma healing alone. Building a support system of trusted friends, family, or peers can be incredibly beneficial. Support groups, whether online or in person, can provide understanding, validation, and encouragement from people who have similar experiences. Having others to lean on can help reduce feelings of isolation, which are typical for people managing trauma responses.

Join a community of like-minded women at Monima Wellness, where you’ll find understanding, support, and healing strength. Contact us today to take the next step in your recovery.

Start Your Healing Journey Today

At Monima Wellness, we understand how deeply trauma can impact your life, and we’re here to help you reclaim control. Our specialized outpatient programs for women are designed to support you in healing from trauma with compassion, personalized care, and proven therapies.

Don’t let trauma responses dictate your future—reach out to Monima Wellness today and take the first step toward recovery.

Call: 858-500-1542 | Verify Insurance

Trauma Response Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ’s)

1. What are examples of trauma responses?

Trauma responses are automatic reactions triggered by the mind and body when faced with a perceived threat, often stemming from past traumatic experiences. Common examples include:

- Fight: Displaying aggression, anger, or irritability.

- Flight: Avoiding situations or experiencing anxiety.

- Freeze: Feeling paralyzed or unable to act.

- Fawn: Trying to please others to avoid conflict. These responses are typically unconscious efforts to protect yourself and can persist even when there is no immediate danger.

2. Is overthinking a trauma response?

Yes, overthinking can be a trauma response. It often occurs as the brain becomes hyperactive in an attempt to predict or solve future problems to prevent harm.

This can manifest as a flight or freeze response, where individuals analyze every situation excessively to feel in control. Overthinking may also serve as a defense mechanism to avoid uncomfortable emotions tied to trauma.

3. What does it mean to have a trauma response?

Having a trauma response means your body and mind are reacting to situations as if they are dangerous, even if no real threat exists. Reminders of past trauma trigger trauma responses and often lead to behaviors such as heightened anxiety, avoidance, or emotional overreaction. These reactions can impact your daily life, relationships, and overall security.

4. Is ADHD a trauma response?

Although ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder, trauma can mimic or intensify ADHD-like symptoms. Trauma may lead to difficulties with focus, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, all of which overlap with ADHD traits.

Trauma disrupts brain processes involved in attention and concentration, but it’s important to note that ADHD and trauma are distinct conditions. A professional evaluation is necessary to determine whether symptoms are trauma-related or ADHD.

5. What are the four types of trauma responses?

The four primary trauma responses are:

- Fight: Reacting to perceived threats with aggression or a need for control.

- Flight: Avoiding situations that feel unsafe, often leading to anxiety or panic.

- Freeze: Becoming stuck or paralyzed in the face of danger, unable to act.

- Fawn: People-pleasing to avoid conflict, often at the cost of personal boundaries. These responses are survival strategies meant to protect, even when the threat is no longer present.

6. Is sleeping with the TV on a trauma response?

Yes, sleeping with the TV or background noise on can be a coping mechanism for individuals with trauma. This behavior often stems from hypervigilance, in which the brain remains alert even during rest.

Silence may feel unsafe, so background noise provides comfort and distraction, making it easier to fall asleep by reducing the anxiety associated with quiet environments.

7. How do you calm a trauma response?

Calming a trauma response involves grounding techniques that bring you back to the present. Deep breathing, mindfulness, and progressive muscle relaxation can slow the body’s stress response.

Working with a therapist can help develop personalized strategies to manage triggers in more persistent cases. The key is recognizing when a trauma response is occurring and taking steps to regulate your body and mind.

8. What is the “Are you mad at me?” trauma response?

When people refer to the “Are you mad at me?” trauma response, they are usually referring to behavior linked to the fawn response. This reaction involves individuals becoming overly sensitive to others’ emotions, often due to past trauma or emotional abuse.

People who experience this may constantly seek reassurance that others aren’t upset with them out of fear that conflict could lead to danger, abandonment, or rejection. This response stems from a deep need to maintain peace and avoid potential harm, even when no real threat exists.

9. Is continuously thinking everyone is upset with you a type of trauma response?

Yes, constantly thinking that everyone is upset with you is often a fawn trauma response. It can develop in individuals who have experienced emotional or psychological trauma, leading to heightened sensitivity to others’ emotions.

This overthinking often results in seeking reassurance to avoid conflict or rejection, rooted in past experiences where upsetting others led to negative consequences, like punishment or abandonment.

References

1. Kar N. (2011). Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a review. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 7, 167–181. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S10389

2. Melegkovits, E., Blumberg, J., Dixon, E., Ehntholt, K., Gillard, J., Kayal, H., Kember, T., Ottisova, L., Walsh, E., Wood, M., Gafoor, R., Brewin, C., Billings, J., Robertson, M., & Bloomfield, M. (2022). The effectiveness of trauma-focused psychotherapy for complex post-traumatic stress disorder: A retrospective study. European psychiatry : the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 66(1), e4. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.2346

3. Boodoo, R., Lagman, J. G., Jairath, B., & Baweja, R. (2022). A review of ADHD and childhood trauma: Treatment challenges and clinical guidance. Current Developmental Disorders Reports. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-022-00256-2

4. McDonald, A.C., Ejesi, K. (2020). When Trauma Mimics ADHD. In: Schonwald, A. (eds) ADHD in Adolescents. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62393-7_13

5. Mazur, M., Jones, D. R., Barnes, S., & Malhi, G. S. (2021). Hypervigilance and sleep disturbances: The interrelationship in PTSD. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 767760. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.767760

6. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2014. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 57.) Chapter 3, Understanding the Impact of Trauma. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207191/